I've talked before about how helpful it is for galleries to offer food and refreshments at openings, that a lot of art seems more beautiful, profound, socially conscious, and politically relevant to the well-fed and slightly tipsy. I lamented the shocking lack of cheese cubes as well as the austere Kruschev-era-style Perrier-rationing at 49 Geary, an unfortunate state of things on its own, but especially piteous in light of something I heard at the most recent first Thursday. A couple of stalwart art lovers who'd attended the monthly art walk since 2001 said that in former days of plenty, not only did the galleries there serve more generous amounts of water, champagne, and wine -- and in glasses made of glass rather than plastic - but in what now seems like an ecstasy of largesse, offered entire wheels of cheese. I was ready to despair that America's best days really were behind it, and that that behind, happily fattened on bries as fragrant as the feet of French angels, had waddled away forever. (continue reading)

I've talked before about how helpful it is for galleries to offer food and refreshments at openings, that a lot of art seems more beautiful, profound, socially conscious, and politically relevant to the well-fed and slightly tipsy. I lamented the shocking lack of cheese cubes as well as the austere Kruschev-era-style Perrier-rationing at 49 Geary, an unfortunate state of things on its own, but especially piteous in light of something I heard at the most recent first Thursday. A couple of stalwart art lovers who'd attended the monthly art walk since 2001 said that in former days of plenty, not only did the galleries there serve more generous amounts of water, champagne, and wine -- and in glasses made of glass rather than plastic - but in what now seems like an ecstasy of largesse, offered entire wheels of cheese. I was ready to despair that America's best days really were behind it, and that that behind, happily fattened on bries as fragrant as the feet of French angels, had waddled away forever. (continue reading)

Tuesday, July 19, 2011

Guerrero Gallery wins the opening party contest. for SF Weekly.

I've talked before about how helpful it is for galleries to offer food and refreshments at openings, that a lot of art seems more beautiful, profound, socially conscious, and politically relevant to the well-fed and slightly tipsy. I lamented the shocking lack of cheese cubes as well as the austere Kruschev-era-style Perrier-rationing at 49 Geary, an unfortunate state of things on its own, but especially piteous in light of something I heard at the most recent first Thursday. A couple of stalwart art lovers who'd attended the monthly art walk since 2001 said that in former days of plenty, not only did the galleries there serve more generous amounts of water, champagne, and wine -- and in glasses made of glass rather than plastic - but in what now seems like an ecstasy of largesse, offered entire wheels of cheese. I was ready to despair that America's best days really were behind it, and that that behind, happily fattened on bries as fragrant as the feet of French angels, had waddled away forever. (continue reading)

I've talked before about how helpful it is for galleries to offer food and refreshments at openings, that a lot of art seems more beautiful, profound, socially conscious, and politically relevant to the well-fed and slightly tipsy. I lamented the shocking lack of cheese cubes as well as the austere Kruschev-era-style Perrier-rationing at 49 Geary, an unfortunate state of things on its own, but especially piteous in light of something I heard at the most recent first Thursday. A couple of stalwart art lovers who'd attended the monthly art walk since 2001 said that in former days of plenty, not only did the galleries there serve more generous amounts of water, champagne, and wine -- and in glasses made of glass rather than plastic - but in what now seems like an ecstasy of largesse, offered entire wheels of cheese. I was ready to despair that America's best days really were behind it, and that that behind, happily fattened on bries as fragrant as the feet of French angels, had waddled away forever. (continue reading)

Monday, July 18, 2011

S*** got real at Cabaret Bastille

Last night’s Litquake event, Cabaret Bastille at Cellspace, was almost a smashing good time. I admit I am disproportionately delighted by parties with costume themes, and there were some glorious vintage and vintage-inspired get-ups. Yvonne Michelle Cordoba (and friend?) performed lovely quasi-burlesque/belly dance at intervals. The problem was that the entertainment emphasis of the night was on the readings (popular contemporary authors reading the works of the lost generation greats). Cellspace is cavernous, and its sound system inadequate for the readings to have been audible to anyone further than four rows back. Except for Alan Black’s bellowing from James Joyce, most of the readings simply didn’t register (through no fault of the readers themselves).

Thursday, July 14, 2011

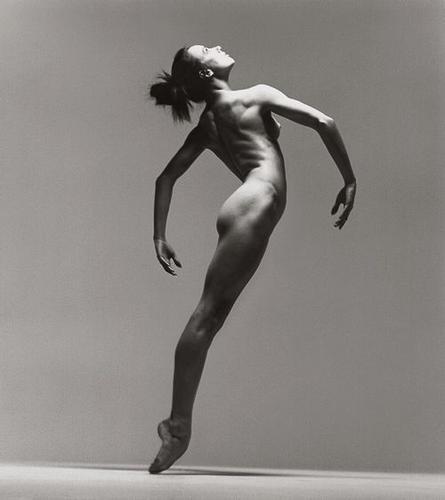

My Review of the Irving Penn exhibit at Fraenkel Gallery in the San Francisco Examiner

If today’s fashion world pushes a narrow concept of beauty — tall, thin, young, more thin — 70 years ago that concept was even narrower, as the tall, thin young girls in the magazines also had to be white.

If today’s fashion world pushes a narrow concept of beauty — tall, thin, young, more thin — 70 years ago that concept was even narrower, as the tall, thin young girls in the magazines also had to be white.For several decades and 150 Vogue magazine covers, Irving Penn worked within these confines to produce images iconic for their beauty and graphical power. Compositions uncluttered by props, and frugal with color (usually black and white) left the simplest and most arresting elements for the eye to focus on: the sweep of a ruched sleeve, the black grid of netting against white plains of skin, the neck as long as the waist, the waist as slender as the neck.

Read more at the San Francisco Examiner:

Monday, July 11, 2011

I compare First Thursday Openings at 49 Geary and the Jazz Heritage Center for SF Weekly

Dear 49 Geary: I'm afraid you just got served.

Dear 49 Geary: I'm afraid you just got served.First Thursdays at the prestigious address are always intellectually, perhaps even spiritually satisfying, not only for art's enriching effect on the mind and soul, but also because, as with any intellectual or spiritual pursuit, you must suffer physical discomforts, deprivations, and abstentions to achieve enlightenment. The elevators are invariably so busy you don't bother to take them from floor to floor in the five-story complex, and instead opt to squeeze past the corridor texters to schlep the cold stone stairs, regretting the high heels you thought looked so Helmut Newton. (continue reading)

Tuesday, July 05, 2011

I write about Purple Rain at the Castro for SF Weekly

Thursday, June 30, 2011

My review of Picasso: Masterpieces from the Musée National Picasso, Paris at the de Young Museum for Art Practical

I paint the way some people write their autobiography…. I have less and less time and yet I have more and more to say, and what I have to say is, increasingly, something about the movement of my thought.

—Pablo Picasso

This collection of “Picasso’s Picassos” comprises 150 of the thousands of pieces amassed by the artist and bequeathed by his heirs to the French government to allay its vampiric inheritance tax. Arranged chronologically, the abridged but representative array of Picasso’s career reflects his belief that painting is “just another way of keeping a diary"; the works become a multifarious self-portrait spanning seventy years. The exhibit begins with what one would swear is a Van Gogh, not merely for its effulgent colors, rough, thick brushstrokes, and the almost material quality of the light beams emanating from the candle, but also for its morbid preoccupation. La Mort De Casagemas (1901) depicts Picasso’s friend and poet, dead from suicide over a failed love affair. Picasso was twenty years old and newly enthralled by the avant-garde movement thriving in his adopted city of Paris; he quickly mastered its various innovations before launching into his Blue Period. (continue reading)

Wednesday, June 29, 2011

My chat with author Wendy Lesser on Shostakovich, SF Weekly

No foreign sky protected me,

No foreign sky protected me,No stranger's wing shielded my face.

I stand as witness to the common lot,

Survivor of that time, that place.

-- Anna Akhmatova, 1961

How does an artist work in the context of an oppressive political regime? This question never loses relevance (since oppression never does either), and it's especially in focus now, with Chinese artist and political activist Ai Weiwei's recent incarceration and release. In Soviet Russia under Stalin's terror, how an artist maneuvered the need for personal expression against the erratic demands of an unpredictably umbrageous state meant the difference between living a pampered (if precarious) life and slavery in the gulag or death. Anna Akhmatova was among the USSR's most celebrated poets, yet her work was repeatedly condemned and censored by Stalin. Dmitri Shostakovich, the era's most famous composer, survived -- not unscathed, and not without being forced to make some risible and humiliating concessions, declarations, and betrayals (his forced public condemnation of the work of Igor Stravinsky he described as "the worst moment of my life"). Author Wendy Lesser has written an account of the artist's personal, professional, and political life as revealed through his 15 quartets in Music for Silenced Voices: Shostakovich and his Fifteen Quartets. (continue reading)

Monday, June 13, 2011

Write-up of the opening night party for "The Steins Collect" at SFMOMA in ArtSLant

Any San Francisco gathering too big to fit inside a bathtub inevitably becomes a fancy dress ball. We love Events and we love to think of ourselves more as participants than as spectators. This held true for the opening night party at SFMOMA for "The Steins Collect."

The great number of people (and the fact that many of them were wearing fancy hats) made getting a good look at most of the art from the formidable, and painstakingly amassed, collection impossible; I enjoyed it the most when I gave up on the art and abandoned myself to bald-faced people-gawking.

The Cries of San Francisco in SF Weekly

You don't have to pick a special day on Market Street to be yelled at by strangers. And it's not that unusual to encounter those in odd outfits trying to sell you objects and services of ostentatious uselessness. But Saturday, the "Cries of San Francisco," put on by Southern Exposure, offered a witty and sometimes touching variant on an old theme based on The Cries of London, Francis Wheatley's seminal 18th-century oil paintings depicting London's street sellers.

You don't have to pick a special day on Market Street to be yelled at by strangers. And it's not that unusual to encounter those in odd outfits trying to sell you objects and services of ostentatious uselessness. But Saturday, the "Cries of San Francisco," put on by Southern Exposure, offered a witty and sometimes touching variant on an old theme based on The Cries of London, Francis Wheatley's seminal 18th-century oil paintings depicting London's street sellers.Thursday, June 09, 2011

My review of Doug Rickard's "A New American Picture" in the San Francisco Examiner

Roofs face the elements without shingles and collapsing, store fronts stand shuttered and windows boarded over, and gingerbread crumbles off formerly elegant facades. In Doug Rickard’s “A New American Picture” on view at Stephen Wirtz Gallery, the sense of desertion pervading the images remains strangely untempered by the spotty presence of people. They amble past decrepit houses and drive on cracked, untended roads. It’s hard to imagine the buses they wait for will arrive. They seem more like trespassers on long-abandoned property than residents of Detroit, Memphis, Fresno and Houston.

Roofs face the elements without shingles and collapsing, store fronts stand shuttered and windows boarded over, and gingerbread crumbles off formerly elegant facades. In Doug Rickard’s “A New American Picture” on view at Stephen Wirtz Gallery, the sense of desertion pervading the images remains strangely untempered by the spotty presence of people. They amble past decrepit houses and drive on cracked, untended roads. It’s hard to imagine the buses they wait for will arrive. They seem more like trespassers on long-abandoned property than residents of Detroit, Memphis, Fresno and Houston.Friday, June 03, 2011

My write-up of "First Thursday" openings at 49 Geary in SF Weekly

Clusters of young Americans propped themselves up on Golgothan stilettos, clutching their plastic cups of white wine with one hand and texting virtuosically with the other. Some hood-ish-looking young men in 'do-rags dragged their pants behind them from gallery to gallery. Many people had expensive-looking priapic-lensed cameras dangling from their necks.

Clusters of young Americans propped themselves up on Golgothan stilettos, clutching their plastic cups of white wine with one hand and texting virtuosically with the other. Some hood-ish-looking young men in 'do-rags dragged their pants behind them from gallery to gallery. Many people had expensive-looking priapic-lensed cameras dangling from their necks.

Thursday, June 02, 2011

My review of Richard Learoyd's Presences at Fraenkel Gallery in Art Practical

It’s hard not to feel like an overzealous dermatologist examining the subjects of Richard Learoyd’s exhibition at Fraenkel Gallery. His large-scale direct-positive images reveal a degree of epidermal detail one usually only gets to see while making out under an interrogation lamp. The shallow depth of field that marks Learoyd’s portraits and that shows imperfections with pitiless clarity—a rough patch here, an incipient pimple there, weirdly dilated pupils—somewhat mitigates the monumental quality lent them by the size of the images and the solid, sometimes brilliant hues he clothes his models in (when he clothes them).

It’s hard not to feel like an overzealous dermatologist examining the subjects of Richard Learoyd’s exhibition at Fraenkel Gallery. His large-scale direct-positive images reveal a degree of epidermal detail one usually only gets to see while making out under an interrogation lamp. The shallow depth of field that marks Learoyd’s portraits and that shows imperfections with pitiless clarity—a rough patch here, an incipient pimple there, weirdly dilated pupils—somewhat mitigates the monumental quality lent them by the size of the images and the solid, sometimes brilliant hues he clothes his models in (when he clothes them).

Saturday, February 12, 2011

On Spectacular Theatre

A few years ago I attended the dress rehearsal of a production of The King and I at the Royal Albert Hall in London. For the most part, it was pleasant, although not being a regular musical theatre goer, I found the echoey effect of the miking on the voices to be distracting. Something else bothered me the whole time, and I couldn’t quite figure it out until late in the performance.

I read somewhere that 3 million pounds ($6 million USD at the time) had gone into the production. Aside from the stars of television and the West End stage who played the King and Anna, and the designers and director, who I know are all paid lavishly compared to performers, I assume the actors, musicians, and techs weren’t paid more than equity wage. It seemed a great portion of the expense went into the set and occasional special effects, which included real fireworks, flaming and fizzing against the vaulted ceiling. To fill the vast Hall (whose rent alone must be staggering) the in-the-round set comprised a convincingly dingy dock and suitably ornate, huge gilt chunks of palace espaliered with silk draping, but the star of the show—the thing most chatted about in the buzzy run-up to opening, was the submerged stage. The entire set perched on beams arising out of real-life, actually-wet, splashable H2O. I couldn’t tell why I resented this, I felt, solecistic bit of reality glistening in the house of make-believe. As soon as I entered the theatre, or arena, more like, before I could swoon over the spectacularity of it all, I had to wonder to myself, “How much must it cost to safely flood the Albert Hall?” But there was something else, unrelated to the display of extravagance which, as an echt poverty thespian I had been taught to disdain, that gnawed at me. It wasn’t even that throughout the whole performance that water was never actually used for anything—not a single pointy Thai model boat made its way through the model canals—thus emphasizing that it was basically a very costly bit of scenery intended to make us go “ooh” and not much else.

No, at one point, Princess Tuptim sat on the dock waiting for her lover, feet over the edge. Her feet didn’t quite reach the water, but she simulated tapping its surface with her toe, in that way that girls do while sitting on docks waiting for their lovers. I realized then why I disliked the set. That actress, tapping the surface of an imaginary pool of water with her toe, was all we needed to know that water was indeed there, to see her watching her reflection corrugate along its ripples, even to hear it lapping. Most theatres have to rely on that alone—the talent of the actor, that is--to make the fake paint-and-plywood world come alive. And part of the thrill of theatre is witnessing that, of recognizing an entire atmosphere from a wave of a hand, or tap of the toe. And in filling the stage with water, making it all so literal, the designers did our imaginative work for us, and robbed us of the thrill of recognition. I emphasize “recognition” because I think that that, as much as any of the beautiful language, music, or profound themes to be found in drama, is what moves us when we see a piece of theatre. What would War Horse have been with real horses? A very nice play about a boy who loves his horse so goshdarn much, through which we’d all have sat waiting for the inevitable equine hard-on or dropped turd. But with the virtuosic level of fakery of the actors manipulating their skeletal puppets to appear to walk, swing their manes, even breathe like horses, we were able to experience the thrill of recognition. That exact way a colt stumbles a bit while trying to stand on its knobby legs, or that special horsey way that horses sneeze, or that bewildered struggle of a horse not made for weight-bearing, dragging a load uphill, all hoofs and ankles digging into the soil—however beautiful it may be in nature, the artful representation reverberates differently in our souls, points our memory to some platonic form of horseyness (er, Equus?) that the “real thing” allows us to ignore. It may be because I’m not particularly an animal-lover, but I found that bit of fakery more affecting than, well, any actual horse has ever been for me. And judging by the wet faces surrounding me at the National that night, I think other people felt the same.

But back to Siam: fittingly, in the same performance, the famous subversive ballet reinforced my point. Without getting into the story too much, I’ll say it ended with the dancers simulating a mass drowning by unfurling a huge swathe of blue silk over their heads to totally cover them, and at the climax, thrusting their hands through hidden holes in the silk, an instantly-recognizable symbol. It didn’t take money or complicated engineering to create, just cleverness and imagination (not to diminute the cleverness and imagination that goes into engineering, but considering how many great shows have been put on in crumbling, sub-code earthquake deathtraps, it is perhaps not the “stuff” of great theatre, unless you’re seeing a show here). The audible, and audibly delighted, gasp in the auditorium at that moment, was, I think, a greater triumph than all of the hype about the flooded stage.

And finally, for all the extravagance of the production, the most affecting moment, and one that incited the audience of thousands to clap along, was “Shall We Dance?”—the exuberant polka that prim Anna teaches the King to dance to. Three million pounds spent on a production and the thing that gets people out of their seats is watching a couple of laughing, panting middle-aged actors gallop around the stage. It was a beautiful, joyful moment, and one in which the only sign that more money than normal was spent was her INSANE DRESS, to which photos do no justice. It was also a moment that did not invite unfavorable comparisons to Yul Brynner (except inasmuch as any comparison to His Bald Majesty in any context must be unfavorable). There’s a famously sexy moment from the movie in which the king insists on dancing as the Europeans do, “not holding two hands”—when Brynner, a masterful physical actor, extends his hand as if it were something else, and fuses it to the corseted waist of the appropriately half-beswooned Deborah Kerr. Daniel Dae Kim seemed to grab Anna’s waist out of pure enthusiasm for the dance itself and his surprise at the suddenly intimate contact, and at Maria Friedman’s visible frisson, made them both for a moment seem like teenagers, and like equals. It had a freshness that can only come from two people standing on a stage, any stage, and allowing themselves to experience something real.

I saw a performance about a year ago at NYU’s summer lab, a workshop for students and alumni of the graduate theatre programs. Everything was as minimal as could be but the talent. It was basically a beautifully written play, acted brilliantly, some of which was due to the talent and skill of the actors and some of course to the director guiding them to make each scene and its place in the story, clear. That was all. Everything else either didn’t exist or had substitutions that were chosen without any attempt at convincing replication at all. Whiskey glasses were jam jars filled with water. Shovels and shoveling were mimed. Bones and skulls were planks of wood and balls of rubber bands. Murders happened with no rupturing of cleverly concealed packets of fake blood. Sound effects were narrated by the stagehand. There was no set, just a stage painted black and a table. It was one of the best, most moving plays I’ve ever seen, and a premier example of how poverty theatre, done well in the aspects that matter (writing, directing, acting), makes a fool of spectacular theatre. I dare any proponent of the hogwash idea that great theatre requires expenditure of fortunes--and that people go to the theatre for the razzle-dazzle, or that cynical, intellectually and creatively lazy cliché, “to escape”—to see something like that and suggest it would have been a more moving experience for the audience if the actors had used real-looking bones and real shovels and real dirt and real fake blood and monstrous set pieces and marvels of engineering and Spielburgian special effects. People who see theatre like this show I saw in the grungy pit at NYU go to the theatre regularly, because it gives them something more substantial than razzle-dazzle (and doesn’t cost $125 a ticket. I’m talking to you, Broadway). People who go to the theatre for spectacle go once a year, because that’s all they need to get their fix of what essentially can only nourish a part of them that doesn’t ask for much beyond the cheap thrill of expensive pageantry. People go to the theatre to be moved in one way or another, and if the only way you are able to move them is with grandiose money-flinging and a literal-minded slavery to realism, you are doing something wrong, and should not be surprised that most people would rather stay at home and watch television.

Unfortunately the production at the Royal Albert Hall was not videorecorded; I would love to include a clip of my favorite moment, although perhaps some of the magic of the live performance would be lost in conversion. So I’m including a clip from the movie. Swoon.

Wednesday, January 26, 2011

Eonnagata, Théatre des Champs-Elysées

Now, I say lucky because I will happily see anything with Sylvie Guillem, of the world’s best legs and worst haircut, although much of the work she’s devoted the post-classical stage of her career to puzzles me somewhat, including this one. Eonnogata concerns the 18th-century diplomat and spy, the Chevalier d’Eon, a famous cross-dresser and possible sufferer of Kallimann syndrome, which prevents the body from developing past puberty. The –“agata” bit came from “Onnagata,” male kabuki dancers trained to perform female roles. Robert Lepage is a noted Quebecois author and director of opera and theatre. He is also 54 years old, thick-waisted, sluggish and I can only assume has bollocks like a woodland caribou. The piece opens on him slashing at the air with a sword, lagging behind the crashing sounds which I suppose were designed to supplement the ferocity lacking in his presence, just as the choppy lighting effects almost mask the phlegmatism of his movements. Maybe he figured that what the greatest dancer of her generation and icon of French sexiness needed was to top off her career by sharing the stage with a pudgy, aging Canadian opera director. The piece proceeded to alternate between superficially realized Japonesque posturing and Rococo embellishments to a lot of incomprehensible storytelling.

Basically, I just don’t see what she gets out of the collaboration. More troubling, I don’t see what her audiences gets out of it, either.

I’m including some footage of Guillem at work, hopefully to show that the merits of her dancing are not merely gymnastic. The extreme arch of her feet, her shocking extension, the sense that she can perform even rapid movements smoothly and gracefully (where lesser dancers seem to have to choose between rapidity and grace)—all serve an expressive purpose, an artistic one beyond merely showing off. When the lines of the body can create a visual illusion that they go on farther than they do (and this, I think ,is the sought after effect of the physical elements considered virtues in ballet, which Sylvie Guillem possesses in spades—the fluid arch of the back and the leg stretched to hyperextension rising to a crest in the arch of the foot), the effect is both thrilling and strangely moving. It’s not just a matter of gawking at someone who can literally kick herself in the face. Dance, like verse drama, is a heightened portrayal of ourselves. In verse drama, we speak better than we really do in order to convey truths that paltry realism can’t carry. Shakespeare tells the truth about us more clearly than our own stammering, clunky inarticulateness ever could. It’s not “realistic” in that we can’t just yammer on and come out with the St. Crispin’s Day speech. But it’s real, as anyone who’s read or heard the speech and felt his throat clench and eyes well up knows. In dance, we need to see the body be more than it is in real life—longer, more graceful, more taut, more expansive, more able to move beyond itself—to perceive what it has to say. Buried in our natural oafishness is the ability to speak through our bodies, to say I am afraid, I am proud, I am sad, I am happy, I am horny, I love you, I want to kill. Dance, at its best, reminds us of that, because when a dancer is conveying these experiences we experience them along with her. And what do we go to the theatre for if not to be moved?

Monday, January 17, 2011

Pina Bausch's Le Sacre du Printemps

I managed to get a ticket to the New Year’s Eve performance at Paris Opera’s Palais Garnier of a modern triple-bill, the piece of most interest to me being Le Sacre du Printemps. Over the phone (at 35 centimes a minute), I was told that the house was completely sold out, but I figured it was worth a try to visit the box office the night of the performance to check for cancellations. There I was told that there were no cancellations but that for 35 euros I could buy a ticket for a seat in which, if I sat, my view of the stage would be completely obscured but if I stood up, I could see perfectly, and since there was no one behind me, I could do that (equivalent seats at Covent Garden go for a quarter of the price but wotevs). I was shown to my seat as the lights went down, the fourth seat in a loge in the upper balcony with a three-quarters view of the stage. My chair had a tote bag in it, and when none of the three other patrons cramped together offered to move it, I picked it up to put it on the floor, at which point the woman in front turned around, grabbed and replaced the bag, then wagged her finger at me. In the darkness I pointed to my ticket and back to the chair, and she responded again with her finger. When I whispered, “This is my seat; I have a ticket for this seat—please move your bag!!” (I didn’t even bother trying to speak French at this point), the man next to her shout-whispered,

“Bee Kwaiaytte!! SHOEUT OEUP!!”

“This is MY SEAT; I HAVE A TICKET”

“SHOEUT OEUP RRAIT NAWW!!”

Apollo is a quieter work for Stravinsky, composed entirely for strings, and so I stomped off in my boots across the noisy wooden floors with the rest of the gallery shoeusheeng me over its gentle opening chords and let the heavy brass door clank shut behind me. After much cajoling, the usher agreed to help me defend my place, but only if I agreed to be verree, verree kwaiaytte. She then realized that she had shown me to the wrong seat (merde alors!) , and that my ticket was in fact for a seat at the far end of the horseshoe-shaped gallery, acutely angled to the stage. I couldn’t see sitting or standing, so I did what most of the people in the ‘gods’ did; I moved over to stand as close to the wall separating the side loges from the central loges as I could. Standing there I could see a little more than half the stage, which I figured was better than being kicked out of the Palais Garnier. I didn’t understand all the commotion over my making noise, however. The upper balconies were pretty noisy. People were talking, walking in and out, burping babies, necking, and openly videotaping the performance. I’ve never had a very strict attitude about audience decorum, except with regard to crinkling candy wrappers and open drunkenness, so I didn’t mind the Freihaus atmosphere of the place, although I did mind that it smelled like a toilet. My visit to the Grand Ballroom during intermission, however, confirmed that the stench pervaded even the high-ticket areas. I feel it’s worth noting that though the Paris Opera might follow dubious standards in bathroom hygiene, they do serve champagne, finger-sandwiches, and petits-fours at intermission, something I have yet to enjoy at Lincoln Center.

I want to talk about Pina Bausch’s Le Sacre du Printemps. I was not familiar with this version before that night. It’s a striking work, which gets certain themes across brilliantly—fear, desperation, the horrific injustices human beings inflict on one another in times of misery. But it doesn’t quite match the big, bad original in several, I think, major ways. This is the opening of Nijinsky's version, originally created for the Ballets Russes:

Nijinsky’s work first tells the story very clearly. At the first lonely, lovely, cadence from the bassoon, the lights rise on people huddled in clusters on the ground. Slowly they arise and stretch, as if out of hibernation. It is the onset of Spring, and the people begin to beat the earth and reach out to the sky, a prayer for abundance. Rival tribes skirmish. The village elder examines the sky for omens. In part 2, the lights rise on the village maidens already engaged in a synchronized, repetitive dance, as if they have been doing this all night. One maiden collapses three times. She is the weakest, the “Chosen One.” She is isolated and forced to perform a frantic, strenuous dance that ends in her death. She is hoisted towards the sky as an offering to the sun-god.

This is the great Beatriz Rodriguez as the Chosen One, in Joffrey Ballet's recreation of Nijinsky's original.

In Bausch’s version, I couldn’t figure out how or why the Chosen One is, well, chosen. I have embedded videos of this version below. The piece opens with a single woman, apparently in some pleasant, maybe vaguely erotic reverie on a red cloth laid out on a stage covered in dirt. Slowly other women emerge from the wings; some rush to a point and stop, others meander, or do slow-motion pliés in the dirt. One can’t really tell what any of them are up to. As the music swells and gets more complicated symphonically, the womens’ movements become more spastic and more stereotypically “modern dance” in effect—they flail their arms and kick at the air, jerk their heads and stare, and it is as yet unclear what their agitation signifies. Is this Spring’s reinvigoration of the earth and people? Is it civil unrest? Is it growing hysteria, heralded by the clarinet verging on overblow in video 1, 2:42? I can’t tell, but that’s not a problem for me—yet. As whatever is happening pans out, the woman who had been asleep on the red cloth wakes from her reverie, and shudders at the realization she is holding this red cloth, which, in a scene entirely in brown and nude, stands out as an obvious, ominous, symbol. The women seem repelled and frightened by the cloth dropped downstage left, and for the first time dance in unison (video 1, 3:45). Also for the first time, there is a sensible (to me, at least) tone to their movements: they beat themselves, hunch their backs, squat and lurch clumsily. It seems more like strenuous manual labor than dance. The dirt from the ground sticks to their skin as they sweat; their hair gets more and more disheveled. They begin to seem less like dancers in delicate flesh-colored gauze slips than like half-naked self-flagellating automatons. One dancer breaks away from the group and shakes, doubling over at the abdomen, suggesting enteric distress (video 1, 4:44). Are these people starving? However, the real menace arrives in the forms of the men, appearing at (5:05)—from the time they arrive onstage it is clear that in this society (if it is indeed a society in the literal sense that is being portrayed here) men have total mental and physical power over the women. They charge onstage and the women suddenly disperse and stare at the floor, looking guilty, and like they hope not to be noticed. The mens’ movements are sharp, athletic, expansive; women cower before them, and seem even more naked in their sheer dresses. The women start to play “hot potato” with the red cloth, which almost makes sense if the red cloth represents the death sentence one expects it to based on both familiarity with the traditional story and on the horror with which it has heretofore been regarded in this version—but at one point a woman grabs the cloth out of the dirt and dances with it. Wait a minute--if the cloth is, say, ‘death,’—like “The Lottery”’s cross-marked ticket, and the women all understandably recoil from it, as they have from its revelation, why does she do that. The men grow more abusive, dragging women across the stage and crowding like wolf packs around the isolated ones. This dynamic persists throughout the rest of the piece, until the choosing of the sacrificial victim, in which each woman, trembling and clutching the red cloth to her breast, approaches what might be some sort of priest or elder (video 3, 4:15), as if to ask whether she is the one who must enact the terrible ritual. Finally the priest ‘chooses’ one (video 3, 5:24), and dresses her in the red cloth, which is in fact a loose-fitting slip. Perhaps it makes sense that a modern female choreographer chose to insert and emphasize an element of male-on-female control and abuse into a story that had heretofore been about something different, but I think it detracts from the main theme of this piece, and the one that this piece can express so well: the power of the group over the individual. You can diffuse that theme with stuff about subjugation of one whole gender by the other, but why would you?

Nijinksy’s original portrays the terrifying Darwinian imperative we arose from: the weakest of the lot is destroyed without mercy or sentimentality. Bausch’s piece hints at various forms of wretchedness (starvation, fear, oppression, displacement--at one point (video 2, opening), all the dancers plod in a circle suggesting a sort of Trail of Tears-style mass exodus—but who can tell what’s going on, really?).

In Nijinksy’s work, on the other hand, the people don’t seem too troubled by anything. Their faces are placid, their movements exact, they are elaborately dressed and made-up and seem healthy, if emotionless. We get the impression that ritual human sacrifice is just these people’s idea of how to keep on keepin’ on. You could easily mistake this society for a fairly civilized one until you realize what they’re on about. It reminds me of the contradictions of ancient Rome—they were so advanced in so many ways, yet eviscerations were their Jersey Shore. There is no hint of any soul-searching, or indeed, of the concept of “soul.” The only fear we see is in the shaking knees of the “Chosen One” after she is chosen: she is the only one who conveys anything we would recognize as human emotion, and she only does that after she has been isolated from the group, the implication being that what we know as “feeling” is a luxury one can only enjoy, or suffer, if isolation from “the group” (or “mob” or “society” or what have you) is not in itself a death sentence. For all this people’s apparent sophistication—they wear clothes, they farm, they organize rituals and pray—they still live like animals of prey. Only the weak separate from the herd and so must die.

My point is that it is less terrifying to see the horrific things human beings do to one another in times of misery than it is too see them doing the same things as mundanities. But I suppose anterior to that, my dissatisfaction with the piece stems from resentment at not being able to tell what is happening on a superficial level, not being able to follow the story or deduce whether there even is a story. If a piece is entirely abstract, then one can give oneself over to be moved by whatever emotions or ideas those abstractions elicit. But if there is a storyline, or even a suggestion of a story, it should be made clear enough to allow us to focus, both intellectually and emotionally, on the themes, on the heightened vision of ourselves that dance can show us, the stuff that’s both higher and more profound than plot. One can’t give oneself over to be moved by portrayals of human experience while simultaneously trying to sort out what that experience is.

I’ve linked to high-quality videos of Tanztheater Wuppertal’s 1978 recording of the piece. Of course the dancers I saw at Paris Opera were slimmer and longer-limbed, but the choreography speaks for itself, and Bausch does choreograph for a diversity of both body type and technique.

Sunday, September 19, 2010

On the rechristening of Henry Miller's Theater *update*

Sometimes I have to agree with Christopher Isherwood. There have been some stupid, crass, and embarrassing decisions made in the renaming of certain Broadway theaters. The renaming of the Plymouth and the Royale theaters after bureaucrats would be the worst examples if there weren’t also a Broadway house named for an airline company nobody even likes to fly with. Henry Miller's Theater was rechristened The Stephen Sondheim Theater the other night. This choice isn’t as bad as the first ones described here, but it is still an inappropriate one, and here’s why:

There’s no Broadway theatre yet named for either Arthur Miller or Tennessee Williams. Now, no matter how much Sondheim lovers love Sondheim, they cannot make a case for him having as great an influence over American cultural life as Williams or Miller. This is not a polemic on the quality of Sondheim’s work; I wouldn’t presume to be able to speak intelligently on the subject, and I have too many sensitive song-and-dance friends who would pout if I did. However, I don’t know anyone who isn’t already a musical theatre enthusiast who knows or cares either way about Sondheim or his musicals. But every American reads Death of a Salesman and A Streetcar Named Desire in school, and there is a reason for that. The influence of these writers and the importance of what they had to say extends beyond the realm of Theatre (where, aside from that Johnny Depp film, and a few episodes of Topper, Sondheim’s influence stops), into that of literature and even the way Americans see themselves. In fact, Arthur Miller reworked the basic formula for tragedy, which had not been tinkered with for over three thousand years, to state that “the common man is as apt a subject for tragedy in its highest sense as kings were.” The “heroic attack on life,” which from the birth of drama had been the exclusive domain of kings and gods, Miller imparted to the unknown, laboring, “small” man—the Willy Lomans, Eddie Carbones, and John Proctors of the world. In his essay, “Tragedy and the Common Man,” Miller writes,

“I think the tragic feeling is evoked in us when we are in the presence of a character who is ready to lay down his life, if need be, to secure one thing--his sense of personal dignity…. the fateful wound from which the inevitable events spiral is the wound of indignity, and its dominant force is indignation. Tragedy, then, is the consequence of a man's total compulsion to evaluate himself justly. In the sense of having been initiated by the hero himself, the tale always reveals what has been called his "tragic flaw," a failing that is not peculiar to grand or elevated characters. Nor is it necessarily a weakness. The flaw, or crack in the character, is really nothing--and need be nothing--but his inherent unwillingness to remain passive in the face of what he conceives to be a challenge to his dignity, his image of his rightful status.”

If it seems strange that that there were ever a question that this “compulsion to evaluate himself justly” is a universal, classless compulsion that drama must portray if it is to reflect the human condition accurately, it is because Miller had the insight to write a tragedy in the high tradition centered not on a king or a prince but on a traveling salesman. Drama has not been the same since.

How often does someone rework something that the ancient Greeks came up with and change it for the better? Not often. But Arthur Miller did. And with it, the way we think about heroism, fate, and the mirage of the American Dream.

We can take for granted that Sondheim changed, revolutionized, even, the musical both stylistically with his non-linear plots (which Miller also did first with After the Fall) and thematically in his divergence from the usual bright fare to darker, more introspective themes (which straight theatre had been doing for, again, several thousand years). But that says more about the musical as being a still-young art form, and about Sondheim’s great influence in helping it catch up with the other arts, than it does about him as an artistic force on the level of artists whose influence does what art should do, that is, change not only the mores and structures of its own genre, but of the society and culture that produced and witnessed it. If you write a book about the Chicago meatpacking industry, and the President of the United States reads it, throws his breakfast sausage out the window, and rallies his administration to create what eventually becomes the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, you have changed culture you live in, maybe even the world. If you create a character who personifies sensitivity, frailty, even spirituality, and place her in a losing match with one personifying brutality, pragmatism, and profanity, you’re holding a mirror up to a society in which those very forces are vying for primacy, and hopefully, inspiring people to guard as well they can what’s sensitive, frail, and sacred. If you write a play that makes not only Americans but people all over the world question the “American Dream” and the moral, human value of the characteristics that help one achieve success in a cold, inhuman, and corrupt system, you change the way people think about their own dreams and eventually, hopefully, how they will act. You have, in a way, changed the world. If you write a musical and it changes musicals, you haven’t changed the world; you’ve just changed musicals. Which warrants a name on a marquee, changing musicals or changing the way America thinks?

Tuesday, March 03, 2009

Can you believe this pretentious fuck?

I found a cafe the other night as I wandered in the Las Huertas neighborhood of Madrid that looked attractive, with a lived-in-looking art deco interior and a free window table like I prefer. I went in and ordered a glass of white wine and prepared to write or sketch in my notebook, for what seemed to be the perfect way to spend my first evening in Madrid. As I waited for my drink, I checked my Timeout guide on the chance that the place, Cafe Central, might be mentioned, and it was, as one of the prime jazz venues in all of Spain. So when the waiter told me that there would be a performance tonight and would I like to buy a ticket, I thought I could painlessly knock off one of my cultural duties as a tourist while simultaneously doing what I'd always rather be doing: sitting in cafe with a notebook. So I bought a ticket and got to “work.” However, as the show was about to start, the lights went down; I could no longer read or write, everyone else in the room simultaneously lit a cigarette, and I could only join the crowd blinking at the stage and try to avoid becoming enraged at the cloud of smoke thickening in the room.

What's worse, then the music started. Apparently, Bob Sands is a well-respected musician, and his quartet quite a hot ticket, although the cafe was not a large venue and wasn't nearly full. I guess when i hear the word “jazz” I always optimistically envision some sort of big band and Sarah Vaughn singing with a flower in her hair. I expect to hear some discernible melody rather than a cacophany of “riffs.”And for the drummer to show some restraint with the cymbal brush. And for one song to sound different from another. Fool.

So already I regretted paying the 11 euros my ticket cost, thinking what a lot of pretentious bullshit jazz is now and wondering if i could blame Miles Davis for this, but THEN--

get this, during the first song, when Mr. Sands was finished with all his frantic riffing, he stepped down from the stage, leaving his remaining trio of minions there to paddle along while he stood off to the side, in full view of the audience, smoking and drinking a beer! Now, I know a jazz performance is often a much more casual event than many other types of musical performances, and that this is indeed part of its charm, but doesn't that just seem unprofessional and bratty to anyone else? He did this during every song for the rest of the show (of course I left early, but i had seen enough). Not once did any of the other musicians get to smoke or drink or bugger off the stage like that when they weren't playing at being a star. Only he did, apparently to make sure everyone knew how much soul he was putting into this instrumental rorschach splatter, so much soul that the minute he was done showing off, he had to go lean against an amplifier and sedate himself. And not only that, but as he was smoking and drinking by the side of the stage and watching the lesser stars, he sort of jived along to their playing—like bobbing his head and swinging his free hand to some rhythm only he was able to identify.

Dear Mr. Sands,

Hello, asshole. I'M YOUR AUDIENCE. I'll be the judge of whether this is groovy or not, you FUCKING PEDANT!

Love, Larissa

Here is a video of him off in the corner. That big empty space is the unoccupied center stage, and that head which in the video you can barely make out bobbing up and down in the doorway is his.

Also, sometimes he would talk to the audience in that jazz station DJ voice, just under the breath a bit (I guess in an attempt at sexy?), speeding up and slowing down at nonsensical places in a way that suggested he'd really rather be scatting. “nowwwwwwwwwwladiesandgentlemenwe'dliketoplayalittlesongforyouentitled,uh-SAAAAAAAAAAAAAANDSvillllllle....uh one, uh two, uh onetwothreefour” I kept expecting to hear “daddy-o” thrown in somewhere. It was hard not to laugh at what, if this were Saturday Night Live, would certainly be a brilliant send-up of jazz musicians everywhere enchanted by their own coolth, but he wasn't joking or mocking anybody. It reminded me of how Rufus Wainwright always sounds like he's doing a hilariously cruel impersonation of himself, except he's not impersonating; he's just being himself, and that aural mix of cat rape and teenage whine is a sound he creates unironically.

And yes, one of the songs was entitled Sandsville. I know...

Wednesday, October 26, 2005

On the Grandeur that is Rome

Back to the story. In a private moment together, Vorenus asks the general and prisoner Pompey how this sad state of affairs could have come to be; “Surely Pompey Magnus had Caesar at great disadvantage…” (though Vorenus knows to whom he is speaking, he respects the great man’s wish to conceal his identity and plays along with Pompey’s insistence that he’s a humble traveling merchant). For a moment, pride at hearing of his past strategic prowess flashes across Pompey’s face in a smile too genuine and immediate to be suppressed, ”Yes, I did, I did…it seemed impossible to lose…” The smile fades, “that’s always a bad sign….” Vorenus notices but does not remark upon Pompey’s slip. Pompey recalls, wet eyed, his early mentorship of Ceasar and draws on the ground with a stick the recent decisive battle between him and his former protégé. In silent flashes across his face we see his admiration for the victor, his frustration at his mens’ retreat, humiliation and fear at having to now beg for the safekeeping of his wife and children (for indeed, a general knows how seldom such pleas are honored), and most moving, recognition of the immensity of the consequences of his downfall, far greater than the mere defeat of a famous general and his army. “That is how Pompey Magnus was defeated,…and how the Republic died…” A horrible and sad understanding passes bewteen the two men before Vorenus, stunned, stumbles off to the camp fire and leaves Pompey trembling on the beach.

In a cast of excellent actors, Kenneth Cranham’s Pompey is so masterfully embodied that even in a scene lacking violence, nudity, or good-looking people insulting each other, I was totally riveted. Cranham looks as W.H. Auden might have looked had a giant thumb descended on his head and squooshed it just a little, displaced body matter filling out a few, but not all of the wrinkles. He deserves an extra large Emmy for his performance, and I am very sorry that Pompey Magnus was beheaded upon arrival in Egypt (oh, the hazards of travel) by one of his own former soldiers and a Roman, as this pesky historical fact (according to the BBC) prevents him from returning in future episodes. His defeat and death made me wonder:

Or

Live a pretty wretched life all around, full of violence, betrayals, dishonesty, failure, and defeat, and somehow, through a miracle, resolve your life on your deathbed in a positive, even joyous revelation, and literally, die happy?